FILA EXPLORA 5JM02588258 Дамски Цвят бежов ▷ Модни Туристически обувки ▷ Обувки Fila в онлайн магазин Sizeer.bg ▷▷

туристически обувки : Helly Hansen Шапка България За жени, Елате и купете нова шапка в нашия онлайн магазин.

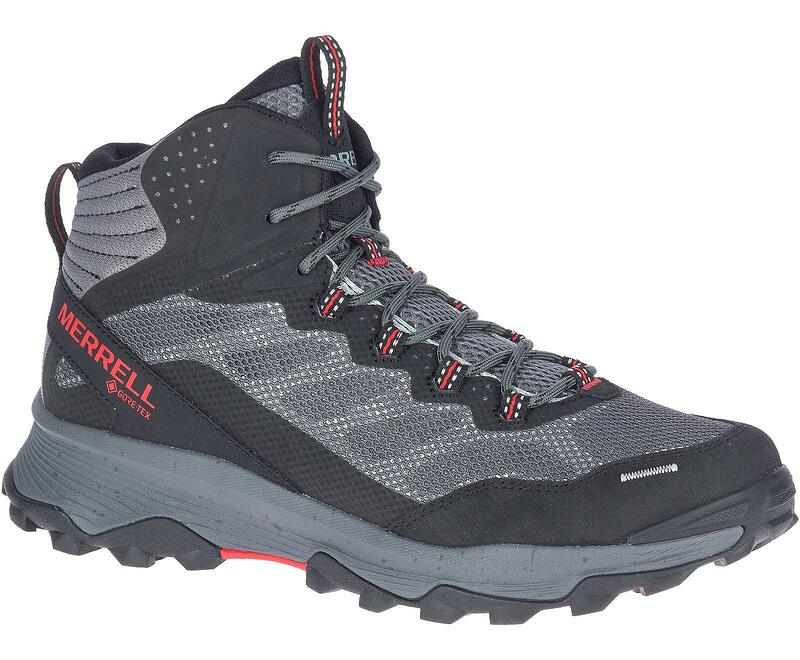

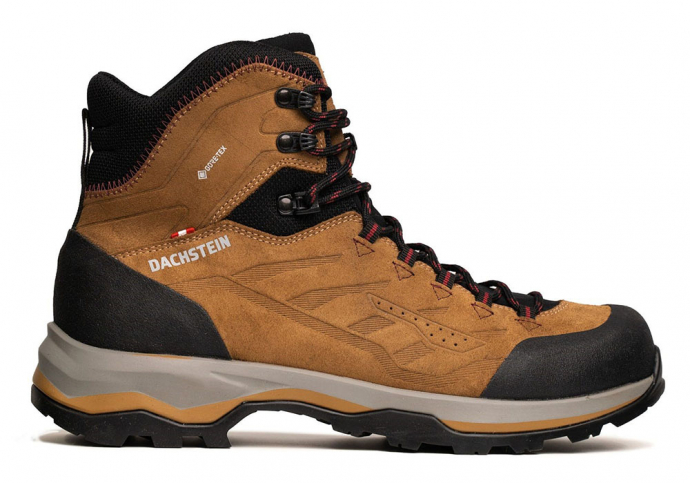

Туристически обувки, категорията включва: високи до средно високи трисезонни и типично летни обувки.

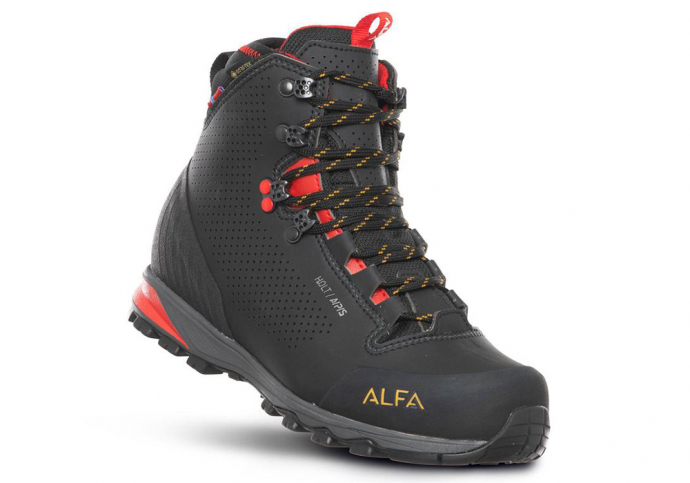

Специализиран магазин за къмпинг, туристическа и зимна екипировка Дамски туристически обувки ALFA Holt APS GTX W Black 2023 | Campingrocks