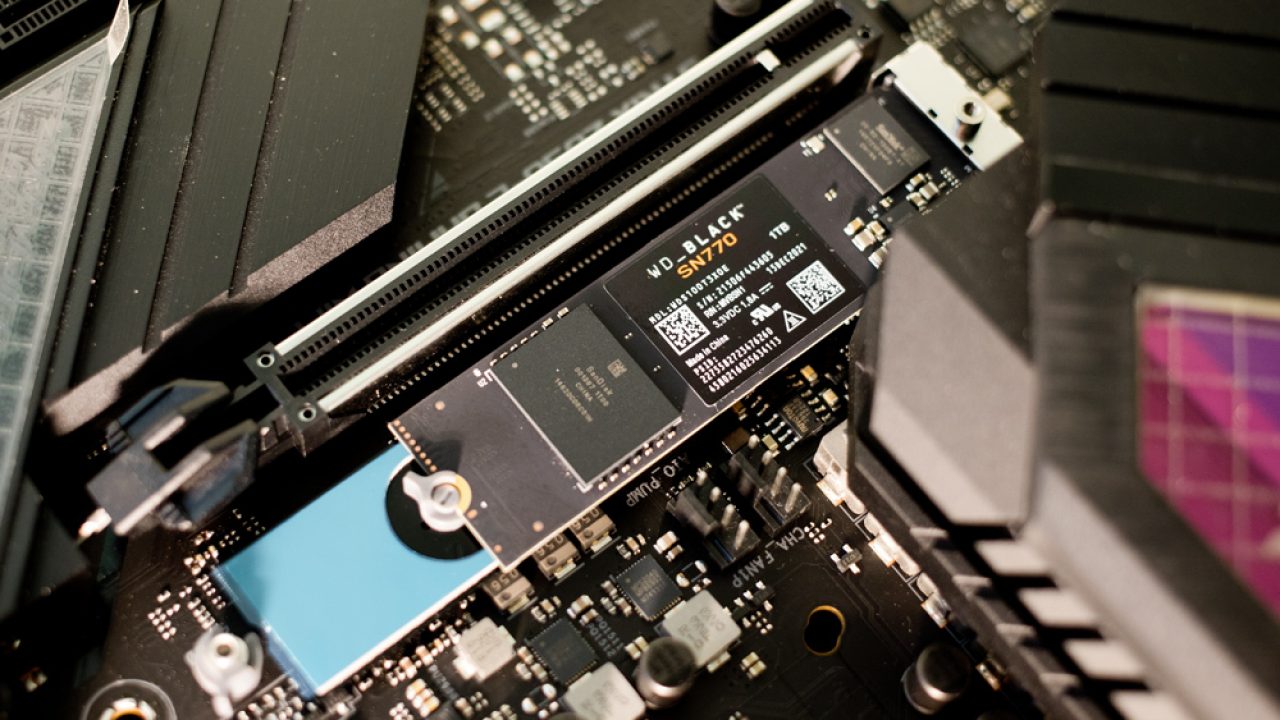

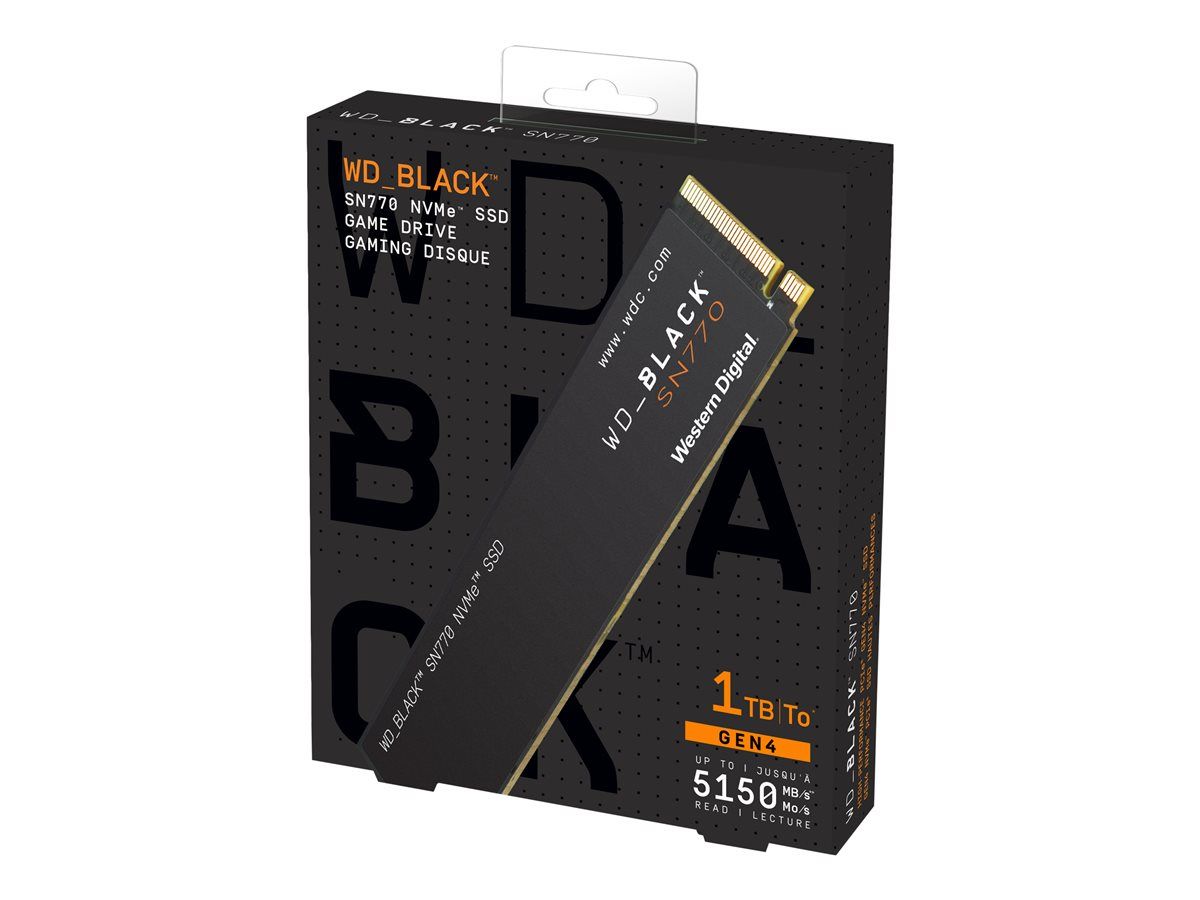

WD_BLACK 1TB SN770 NVMe Internal Gaming SSD Solid State Drive Gen4 PCIe M.2 2280 Up to 5150 MB/s SSD For Laptop Gaming Console - AliExpress

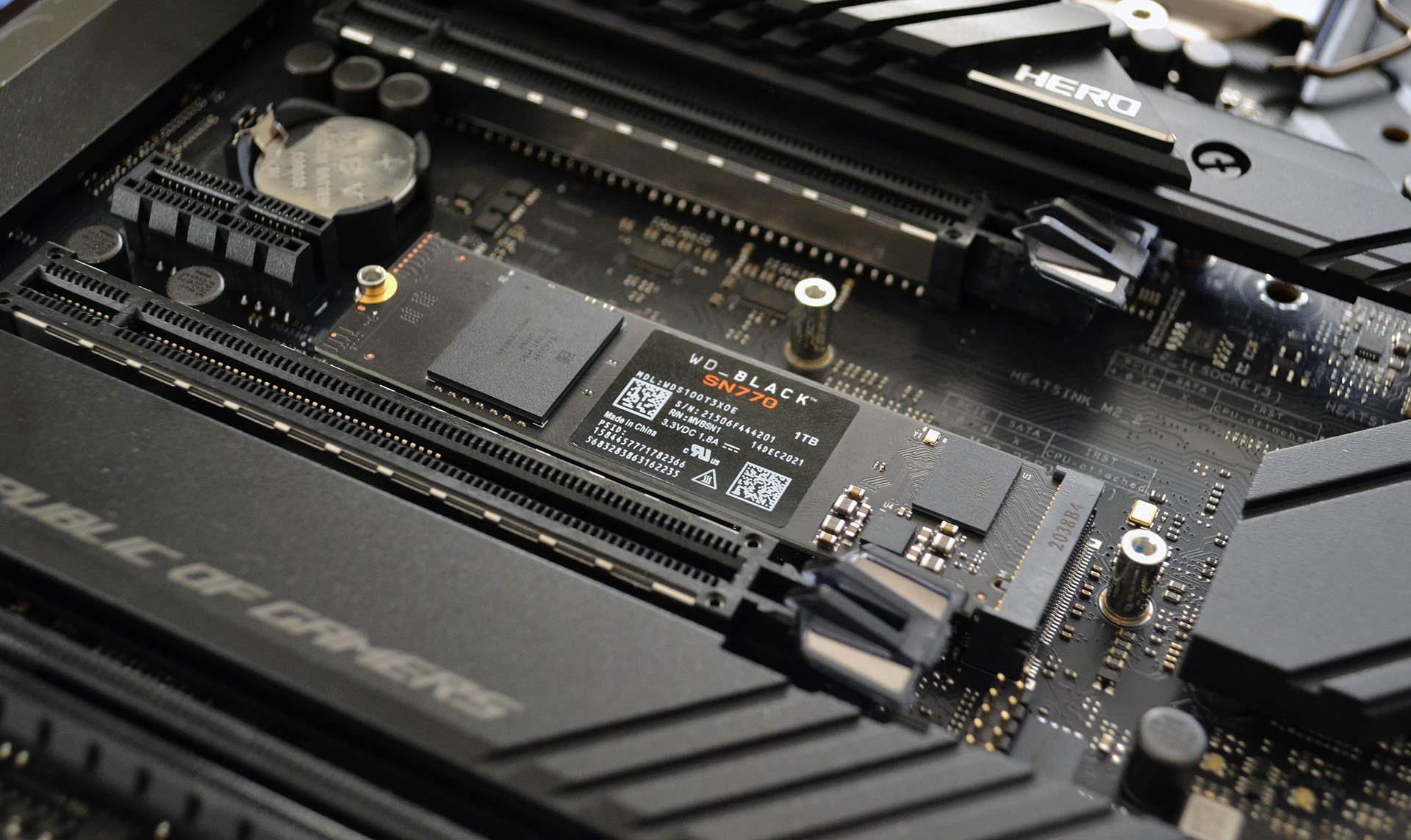

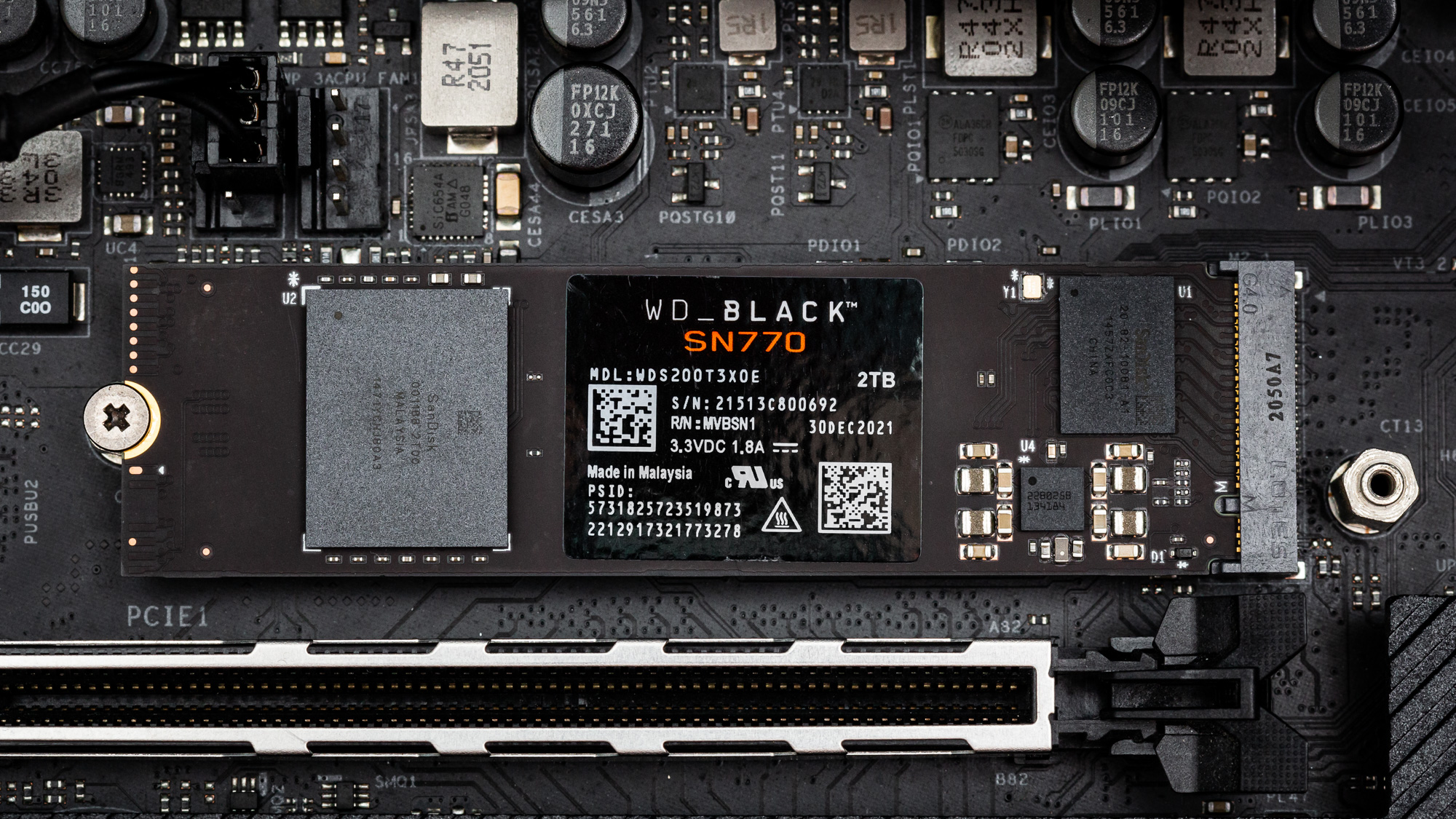

Amazon.com: Western Digital WD_BLACK 1TB SN770 NVMe Internal Gaming SSD Solid State Drive - Gen4 PCIe, M.2 2280, Up to 5,150 MB/s - WDS100T3X0E : Electronics